(Note: This is Part 10 in the series started here. The previous installment is here. In each post, I comment on one of the fourteen points made by Dennis Prager in his article, “If There Is No God.”)

Dennis Prager’s Point #10:

Without God, there is little to inspire people to create inspiring art. That is why contemporary art galleries and museums are filled with "art" that celebrates the scatological, the ugly and the shocking. Compare this art to Michelangelo's art in the Sistine chapel. The latter elevates the viewer -- because Michelangelo believed in something higher than himself and higher than all men. [Note 1.]

I do not dispute Mr. Prager’s denigration of modern art as “the scatological, the ugly and the shocking,” but he misidentifies the root of this cultural phenomenon. The disgraceful procession of trash that has passed for art in the last century or so is not a symptom of the rejection of God but of the rejection of values, which itself has a deeper cause: the rejection of reason. In this, paradoxically enough, the religious have a philosophical root in common with the modern artists who not only generally reject the mind in favor of primal emotions, but spit upon the specific symbols and icons held sacred by the faithful.

This is not to equate the religious with the nihilistic, of course. There is no comparison between civilized, respectful, and thoughtful religious people (like Dennis Prager himself) and the “artists” who see the urinal, with or without a crucifix immersed in it, as a suitable means of expressing their view of mankind. My point is that the antidote for the disgusting bile that is vomited forth from the unfocused minds of modern artists is not faith but reason. Faith unfastens the human mind from the moorings of reality. This is relatively harmless, to be sure, in the average modern citizen, who at most fingers the rosary for an hour on Sundays but otherwise leads a civilized, productive life. But faith also gives rise to other manifestations, including purportedly secular ones, that are destructive. The irrationality that leads some to the Bible or the Zodiac leads others to Dada and the shock-value of sacrilege.

Mr. Prager invokes a popular formulation to indicate the requirements of the great artist - that he “elevates the viewer” because he believes in “something higher than himself.” I am sympathetic to this idea and there is a certain plausibility to it; after all, great art must somehow escape from the trivial, the day-to-day. It should expand to epic scale; it should endure through the ages. The naturalistic banality embodied by modern works like Duane Hanson’s Tourists, for example, sneer at greatness. The random smears of Mark Rothko and drips of Jackson Pollock are so empty of content, they elevate the viewer only in the contortions of logic that they require of him to pretend they belong on a gallery wall.

However, the phrase “something higher than oneself” carries with it two connotations that miss the mark as a proper requirement for works of art. First, there is a suggestion of sacrifice, the idea that men owe their lives and efforts to “something higher”: a god, the state, or one’s fellow men. The phrase also contains a hint of Platonic duality, a severing of the mind and body. The physical, in this view, holds an inferior status to the contemplative. It suggests a disdain for the material needs of man, for his efficacy, for the pursuit of practical values. Both connotations are perfectly consistent with Prager’s religious viewpoint - specifically, the altruist morality and the philosophic intrinsicism of religion, respectively - but are not properly held as prerequisites for great art.

In contrast to Mr. Prager’s formulation, I hold that an artist's works can be great when he is able to express something universal about men. This is not the same thing as “something greater than oneself.” Universals are not “transcendent” in the supernatural sense; properly conceived, they are objectively real abstractions. The pages and canvases of great works of art depict particular characters, events, and images that represent high-level concepts and universal truths. They depict men’s actions and capabilities, his victories and follies.

For religionists, the realm of universal truth is some supernatural dimension; for modern artists, there is no universal truth (with the exception, perhaps, of man’s depravity, misery, and helplessness). Neither perspective is correct. Great art should convey man’s rationality, not his superstitions; it should present his suitability for living in this world, not his dismissal of reality for a mystical paradise.

Figure A - Christ Washing the Feet of St. Peter; (top) from Gospel book of Otto III, ca. 1000 AD, (bottom) from Sadao Watanabe, 1992. Does either of these “elevate the viewer”?

Dennis Prager’s choice of example actually serves to subvert his point. He cites Michelangelo’s work in the Sistine Chapel as being great art - which, of course, it is. But does Michelangelo represent a truly Christian viewpoint or the opposite?

My claim is that from a broad historical perspective, the effect of Christianity on art is the same as its effect on all cultural matters, and for the same reasons: namely, it was detrimental and corrupting. “More than any other form of human expression,” wrote Leonard Peikoff, “art is the barometer that lays bare a period’s view of reality, of life, of man.”[Note 2.] The rise of Christianity signaled the turn of men away from reason to faith, from rationality to mysticism, from earth to heaven... and European art reflects this.

In Greece of the 5th-century BC (with particular emphasis on before Christ), man was a virtuous, noble, thinking hero. It is here that great art was born, along with philosophy, history, and science. Christianity interrupted and reversed this development, consigning man to his divine status as a puny, groveling slave. Then, in the Renaissance, man was reborn as a rational, efficacious hero once more. The Renaissance was, in philosophic terms, a throwing off of the chains of feudal Christendom and a restoration of the pre-Christian Greek ideals. Sure, the exemplary figures of the Renaissance had the superficial vestiges of Christianity - how could it be otherwise after a thousand years of Christian domination? - but the essence of the Renaissance was a rediscovery of reason.

If Mr. Prager wanted to demonstrate art inspired by God, why did he choose a Renaissance artist - arguably, the greatest Renaissance artist - and not choose art from a period that was informed uniformly by religious devotion? There are countless examples of great historical and artistic significance to be found from medieval architecture, sculptures, mosaics, tapestries, and paintings. Why choose the Adam of the Sistene Chapel (Figure B) instead of the Adam of the Hildesheim Cathedral (Figure C)? Surely the latter conveys the cringing humility that is expected of the pious. Mr. Prager ought to regard Michelangelo’s Adam as demonstrating a blasphemous equality with God, bursting with the Promethean qualities that Prager condemns in point #12 as “hubris.”

Figure B. Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam. (Image credit below.)

Figure C. Adam and Eve Reproached by the Lord. (Image credit below.)

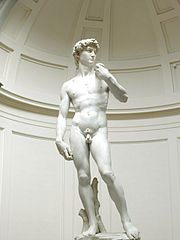

Of course, my questions are rhetorical. Mr. Prager chose Michelangelo precisely in order to artificially prop up his religious argument with the creations of a reasoning genius. The ambiguity of who created whom in The Creation of Adam is a product not of Christian devotion but of the rebirth of reason. The figure of Michelangelo’s David (Figure D) cannot be squared with a religious viewpoint; deference, humility, and obedience are utterly absent from its aspect. It is impossible to imagine this figure with a bowed head or bent knee. This titan could serve neither man nor god; he is his own master. We see in David independence, competence, thoughtfulness - a profound and serene confidence. If there were ever a phrase that David would not accept it would be this: that something is "greater than himself" or "higher than all men."

Figure D. Michelangelo, David. (Image credit below.)

It is plainly not true that without God, there is “little to inspire people to create inspiring art.” The subject and inspiration of great art is properly man and his reasoning mind. True, God - or more specifically, man’s relationship to his gods - has been the subject of many great works of art. But many more great works have nothing to do with God. Revolution, war, leadership, industry, productivity, justice, and revenge have inspired great works of art. And let us not forget romantic love, filial love, fraternal love, and maternal love (not to mention hatred).

If faith is the inspiration for great art, we should expect the greatest art to have emerged from the periods and locations in which faith or anti-reason dominated: the Dark and Middle Ages in Europe, the Orient, the Weimar Republic, and today, from Iran and Afghanistan. If, on the other hand, reason is the inspiration for great art, we should expect the greatest art to have emerged from those places and times in which reason was valued: ancient Greece, and Europe of the Renaissance and Enlightenment.

History has given us the answer.

(Note: The next installment in the series is here.)

NOTES

1. Dennis Prager, “If There Is No God,” http://townhall.com/columnists/DennisPrager/2008/08/19/if_there_is_no_god.

2. Leonard Peikoff, The Ominous Parallels, Penguin Putnam, Inc., New York, 1982, p.161.

IMAGE CREDITS

Figure A. (top) Christ Washing the Feet of St. Peter, from the Society of Clerks Secular of Saint Basil, http://www.reu.org/public/Iconholy/Jesus/ChPeterFeetOtto.jpg.

(bottom) Sadao Watanabe, Christ Washing the Feet of St. Peter, from the Scriptum Modern Japanese Prints, http://www.japaneseprintart.com/images/prints/watanabe%5Fchrist%5Fwashing%5Fpeters%5Ffeet%2Ejpg

Figure B. from Wikipedia entry for “The Creation of Adam,” Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/73/God2-Sistine_Chapel.png

Figure C. from Encyclopaedia Britannica, Adam and Eve Reproached by the Lord, http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/91/3991-004-E18BF0E9.jpg

Figure D. from Wikipedia entry for “Michelangelo,” http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Michelangelos_David.jpg

6 comments:

First, let me say that I’m happy to read that neither you nor your blog has died. Secondly, I thought this was an excellent refutation of Prager’s point.

I was shocked, however, by this combination of ideas: “Faith unfastens the human mind from the moorings of reality. This is relatively harmless, to be sure, in the average modern citizen, who at most fingers the rosary for an hour on Sundays but otherwise leads a civilized, productive life.” The first sentence is a strong metaphorical indictment of operating one’s life based on faith. The sentence immediately following it leads one to believe that this break from reality is generally okay.

Do you care to explain those ideas further?

Thanks for the comment. I'm glad you brought that point up because I certainly do not want to sound wishy-washy on the matter of faith.

By saying, "this is relatively harmless," I meant that the casual and compartmentalized manner in which the typical American holds religion today is relatively harmless compared to the nihilism embodied in modern art.

I do think one does harm to oneself if any amount of faith is permitted to corrupt one's thinking, since it stunts and distorts one's connection to the real world, which in turn negatively impacts one's survival and happiness. (As an aside, Harry Binswanger once pointed out that "faith" doesn't even refer to any thought process in particular, but is really just the absence of thinking: evasion, laziness, etc.) In these minor, compartmentalized cases, I think it is the faithful themselves that suffer and pay the consequences - at least the direct ones. In terms of political freedom, at least, one has a right to believe whatever one wants, provided his actions harm no one else.

The reason I included that sentence in the first place is that one of my goals in this series was to reach some people who hold religious beliefs but are honestly trying to understand if their beliefs are valid. I think it would simply be off-putting to say to the average American that goes to church on Sunday that he is the same as the "artists" that created Piss Christ. That is simply not true.

However, what is true is that faith and nihilism are two forms of rejecting reason. Little harms and big harms are still harms. I do not mean to soft-pedal "minor" instances of faith; the religious reader must either confront the essence of faith or evade it.

Great article!!! You say that, "For religionists, the realm of universal truth is some supernatural dimension; for modern artists, there is no universal truth (with the exception, perhaps, of man’s depravity, misery, and helplessness). Neither perspective is correct. Great art should convey man’s rationality, not his superstitions; it should present his suitability for living in this world, not his dismissal of reality for a mystical paradise."

Paraphrasing Ayn Rand: To create great art would "require more than a beard, aguitar or a bible."

Great article111 You said, "For religionists, the realm of universal truth is some supernatural dimension; for modern artists, there is no universal truth (with the exception, perhaps, of man’s depravity, misery, and helplessness). Neither perspective is correct. Great art should convey man’s rationality, not his superstitions; it should present his suitability for living in this world, not his dismissal of reality for a mystical paradise."

To paraphrase Ayn Rand: To create great art would "require more then a beard, a guitar and a bible".

Thanks for the comment, pomponazzi. Ayn Rand was speaking of revolutions when she wrote, "What this country needs is a philosophical revolution... a reassertion of the supremacy of reason, with its consequences: individualism, freedom, progress, civilization. But this will take more than a beard and a guitar."

The context of the quote makes clear that the "beard and guitar" is referring to the bankrupt intellectuals of the New Left. This does apply, as you noted, to the art world, in that 20th-century art reflects the cultural disintegration and anti-reason mentality of modern times.

British philosopher AC Grayling said much the same thing, and it is one of the few things I can actually remember him saying (most of his stuff is just very bland popular-philosophy stuff).

He admitted that, yes, the great cathedrals, the statues, the art works, the choral music... it all might be rather splendid. But imagine if Christianity never became that wide-spread, and before secularism grew, the Greek paganism was the cultural now. How much greater would it be, if the cathedrals were temples to the ambitious Icarus, or the choral music rousing songs of the Odyssey, the statues - like David - depictions of heroic mortals!

Post a Comment